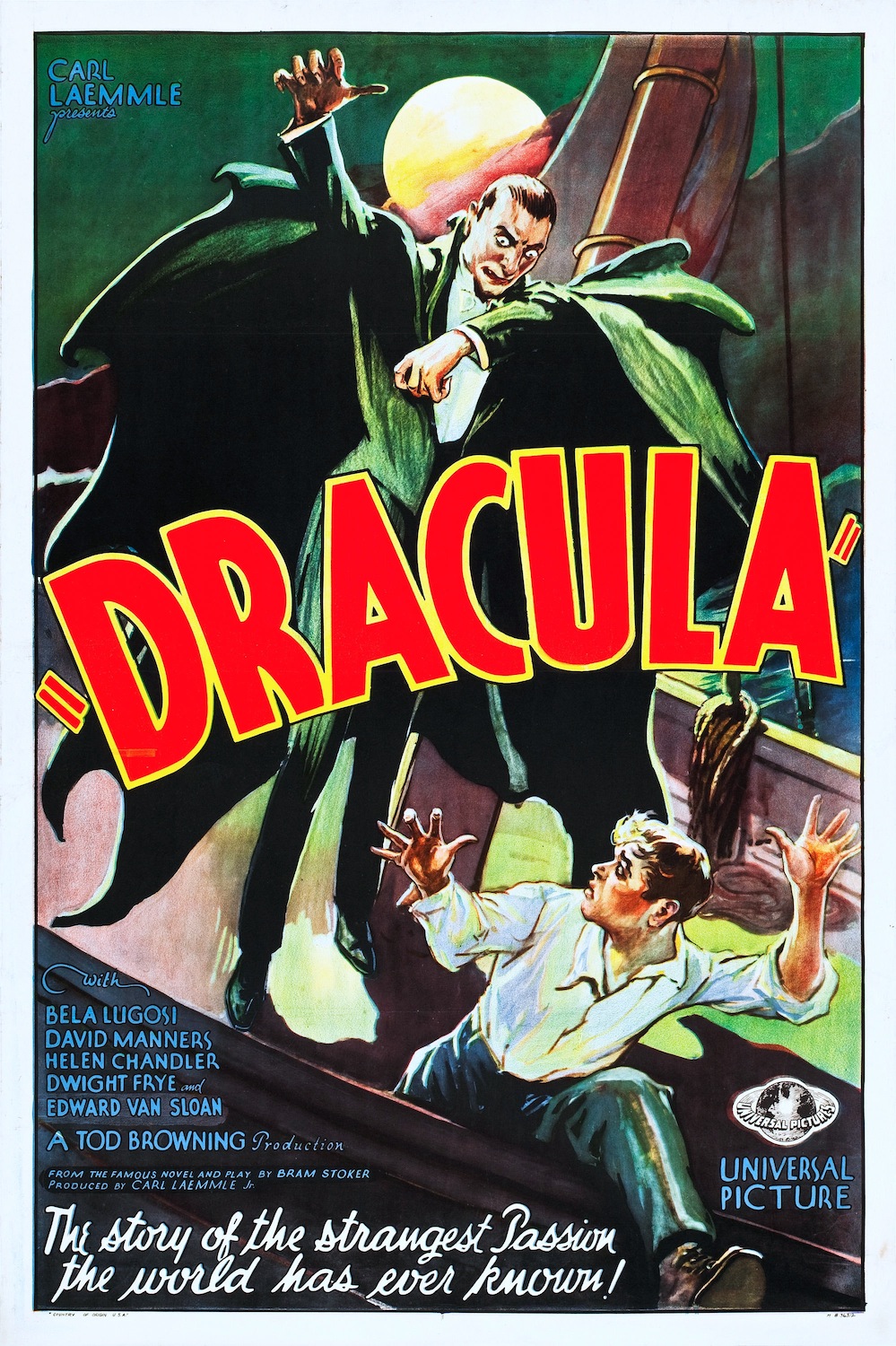

Classic Horror Movie Night: Dracula, 1931

Some actors become so indelibly associated with their most famous roles it becomes difficult for audiences to accept them in any other part. Although Bela Lugosi made nearly 70 more films in the 28 years after he first sucked blood in Dracula (1931), among them Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939), few filmgoers today remember him in a single one of them (except, perhaps, his last, the bizarre cult classic directed by Ed Wood, Plan Nine from Outer Space, 1959). Typecasting is an inherent danger for any star; for Lugosi, it crept strangely into his private life as well. For many years, he appeared in public in his trademark costume and demeanor, and was even buried in Dracula’s black cape. When he looked in the mirror, did he only see the Transylvanian count staring back at him? Or, like the vampire character he portrayed, did he see nothing at all?

It would be a mistake to write Lugosi off as merely eccentric or deranged (and thankfully we have Martin Landau’s Oscar®-winning role as the actor in Ed Wood (1994), to provide us with a richer, more human portrayal). Born in Budapest, Hungary, Lugosi was a classically trained actor who took on a variety of roles in his native country and Germany. After World War I, he migrated to the U.S., where he played a number of romantic leads on stage and film. In 1927, he was cast in the title role in the stage version of Bram Stoker’s classic vampire tale. The play was a tremendous hit and ran for three years. But even after that success, Lugosi was not the first choice for the film version. When studios first started clamoring for the screen rights, a number of actors, including Paul Muni, were considered. Universal first intended to make the picture with Lon Chaney, under the guidance of Chaney’s frequent director, Tod Browning. Chaney’s death put an end to that possibility, and after much pleading and lobbying by Lugosi (in which he sought the aid of Stoker’s widow) and offers to do the role for a mere pittance, the studio decided to give him the part.

Universal had considered doing the story years earlier, but many script readers found it too repulsive and disturbing for general audiences. They were proved wrong on its release; Dracula became a huge hit, rescuing the financially troubled studio and ushering in its string of 1930s horror classics, a trend solidified by the release the same year of Frankenstein (1931). Besides Lugosi’s memorable performance, the film’s success can be attributed largely to the work of its director and cinematographer. Browning had distinguished himself as a director of complex, atmospheric silent thrillers at MGM, particularly the 11 collaborations with Chaney, among them The Unholy Three (1925), The Unknown (1927), and London After Midnight (1927). Dracula became his most successful and lasting film, matched in film history only by what many consider his masterpiece, the unique and astonishing Freaks (1932). But he, too, became more or less typecast as “the Edgar Allan Poe” of cinema, and when the Universal horror cycle ran its course by the end of the decade, he was no longer considered an A-list director (this was a fate shared by his rival, James Whale, a director of great taste and eclectic vision who never escaped the trap of his successful Frankenstein films). Browning retired after his last movie, Miracles for Sale(1939) and did not work in motion pictures for the remaining 23 years of his life.

The opening sequence of Dracula, with its Transylvania setting, is among the finest work Browning ever did on screen, and it owes much to the cinematography of German-born Karl Freund, an Academy Award-winner for The Good Earth (1937) who completed his career lensing various television shows, most notably I Love Lucy. These first 20 minutes are predominantly silent – in fact, beyond a few snatches of Tchaikovsky and Wagner, there is no background music in the film at all. A rising sense of dread is accomplished by the creaking sounds of coffin lids and by Freund and Browning’s floating camera creating an atmosphere of mystical terror reminiscent of the German silent fantasies. After that, when Dracula has migrated to England in search of new blood, the movie betrays its stage bound roots (Browning chose to stick rather closely to the stage version instead of going back to Stoker’s richer novel). At this point, the focus shifts to Lugosi’s performance.

Prior to the film’s actual production, an article in the Motion Picture Herald announced that Lew Ayres had been cast opposite Helen Chandler and that the film would be both a thriller and a romance. But by the time the cameras began rolling, Ayres had been replaced with David Manners and Browning dropped the romantic angle. According to David J. Skal and Elias Savada in their biography, Dark Carnival: The Secret World of Tod Browning,Dracula was filmed between September 29 and November 15, 1930, with additional scenes and retakes on December 13, 1930, and January 2, 1931. According to David Manners, the production was “extremely disorganized.” Asked about the experience of working with Tod Browning, Manners laughed and said, “It’s funny you should ask. Someone asked me the other day who directed [Dracula] and I had to say, I hadn’t the faintest idea!” Manners stated that, “the only directing I saw was done by Karl Freund, the cinematographer.”

In his definitive biography on Lugosi, The Count, writer Arthur Lennig wrote that Universal “spent a considerable sum on the giant sets for Dracula’s Transylvanian castle and British abbey. After the film was completed, the castle set remained standing and was still being used more than ten years later: At the end of Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1942) some scenes take place among its “broken battlements.” The propmen searched around for exotic old furniture, the technicians spun an eighteen-foot spider web made out of rubber cement that was shot out from a rotary gun, and masons built a giant fireplace big enough for a man to stand in and placed a real fire in it. Unfortunately the fire created some difficulties. The crackling of the wood made so much noise that it was picked up by the rather unselective microphones then in use, and the dialogue scenes had to be postponed until the fire died down.”

Since the release of Dracula, there have been countless other vampire movies and remakes of Stoker’s original novel. Yet for most people, the look and sound of a true blood-drinking Transylvanian noble will always be Bela Lugosi. His thick Hungarian accent and lack of fluency in English forced the actor to learn his stage lines phonetically. As a result, the character’s halting, over-deliberate words seem to be not the result of an actor’s verbal difficulties but the guarded mystery of an exotic character carefully concealing deadly secrets. Lugosi once said he made a deliberate choice not to lose his accent (because his fiancee liked it). That may have been as big a mistake as his refusal of the role of Frankenstein’s monster, a part that may have further locked him into the horror cycle. At least it would have provided a radically different view of him in the minds of the public and film executives. But it was Boris Karloff who got his break in Frankenstein after Lugosi turned it down and quickly became the bigger star. Although typecast in horror and thrillers himself, Karloff was offered more and better roles, and earned greater money while Lugosi filed for bankruptcy only a year after Dracula was released (the picture made a fortune, but the actor’s take was only $3,500). Lugosi often appeared second-billed to Karloff, and eventually (and unmemorably) played the monster in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). He died penniless and addicted to drugs in 1956.

An interesting side note about the Dracula production: after Browning completed each day’s work, directors George Melford and Enrique Tovar Avalos came onto the same sets and filmed a Spanish-language version at night.

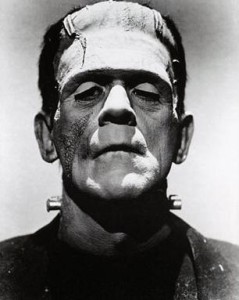

Classic Horror Movie Night: Frankenstein, 1931

Director James Whale’s adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein became an instant horror classic when it premiered in Santa Barbara in 1931. As remarkable for its grasp of elemental horror as it is for its visually arresting set design, the groundbreaking Universal film set a new standard for the genre that has continued to influence contemporary film.

Frankenstein opens on an eerie, atmospheric note at a hillside funeral that looks like a set piece for the German Expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). Whale, in fact, screened Caligari as well as The Golem(1922) and Metropolis (1927) to refresh his memory of German Expressionism, a notable influence on the striking look of his Frankenstein.

Assisted by the hunchback Fritz (Dwight Frye), probably the most famous mentally deficient sidekick in horror cinema, Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive) can be seen in the film’s opening waiting for the funeral to end so that he can dig a freshly buried corpse out of its final resting place before skulking back to his gothic lab. That night Dr. Frankenstein sends Fritz to a local university to carry out the final step in his reanimation project — to steal a brain to use in their experiment crafted from stitched-together corpses. But Fritz mistakenly selects an “abnormal” criminal brain, which when placed in the creature unleashes terror on their small Bavarian village.

The scene where the Monster inadvertently drowns a village girl Maria (Marilyn Harris) was deemed too shocking and deleted from the film upon its original release, though it was later reinstated. Mindful of the macabre aspects of its production, Universal also added a prologue to the film, spoken by Edward Van Sloan (who also provided an epilogue, now lost, to Dracula,1931) was also added, to warn viewers of the shocking nature of what lay ahead.

Though Frankenstein had been made into other film versions, including a 1910 Edison Company production, a 1915 version called Life Without Soul and the Italian Master of Frankenstein in 1920, none of them offered as memorable a movie monster as the one created by Boris Karloff. And though a flurry of movies were inspired by Whale’s penultimate horror film: The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) and many others, none has yet matched the original power of a film which broke important ground in two regards: in its representation of a scientist who tampers with power reserved for God and of a monster who is not entirely evil, but has sympathetic qualities too.

Tod Browning’s Dracula, released 10 months prior to Frankenstein, had a significant impact on Whale’s film. Dwight Frye, as Fritz, had also played Dracula’s half-wit assistant Renfield in Browning’s production of Bram Stoker’s novel and that film’s Van Helsing – Edward Van Sloan – was recast in Frankenstein as Dr. Waldman. And Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula was so memorable and successful in that film he was initially cast to play the Monster in Frankenstein. Lugosi, however, was said to be outraged by the prospect of playing such a one-dimensional half-wit, preferring the role of Dr. Frankenstein. Nevertheless, he attempted to play the monster but his interpretation was deemed too sensitive and understated. Though Shelley’s 1816 novel had featured a sympathetic monster, Universal wanted a more sinister creature so they hired 43-year-old B-movie veteran Karloff to play the role and the actor worked hard with Universal’s makeup artist Jack Pierce to insure that their malevolent creation would be unforgettable.

Pierce, who also created the look of Bela Lugosi’s Dracula, researched the look of the Monster for three months. Pierce studied anatomy, surgery, medicine, criminal history, criminology, burial customs and electrodynamics, before he even began the grueling daily 5 hour make-up application (followed by two hours of make-up removal) to create Frankenstein.

As part of creating this innovative movie monster, Karloff was also given boots to increase his height to seven feet six inches. The boots weighed a cumbersome 30 pounds, and were combined with steel struts on Karloff’s legs to give the reanimated beast his signature lurching walk, part nightmare, part toddler. Ultimately, this Monster created by Karloff, Pierce and Whale did have poignance and played upon viewers’ sympathies, causing some to see the Monster as a stand-in for the troubled director himself, who also yearned for understanding.

The struggle of bringing this monster to life on the screen was considerable and caused Karloff to lose 20 pounds over the six weeks it took to film Frankenstein. The strain of carrying Dr. Frankenstein to the summit of a windmill at the film’s climax was so great, in fact, that Karloff required hospitalization for back problems.

Though Karloff’s performance went unappreciated by the Universal Studios executives, which even excluded the actor from the movie’s premiere, Karloff sufficiently impressed his movie audiences. Many viewers were reportedly so terrified by his appearance they fled from the theater in fear. Karloff called the Monster his favorite film role and film history has tended to agree with him — the actor was identified with the part until the day he died.

In addition to its classic status in the annals of movie making, Whale’s Frankenstein was an enormous financial success. Made for only $250,000, the film returned $12 million upon its release.

The production history surrounding Frankenstein is as fascinating as the film itself. Bette Davis was initially considered for the role of the delicate Elizabeth, but Whale — probably rightly — believed that Davis was too aggressive to play an ethereal horror movie victim. Instead, Mae Clarke was tapped for the role, an actress best remembered as the dame who gets a face full of grapefruit from James Cagney in The Public Enemy (1931).

Though referred to simply as “the Monster” in Shelley’s novel, it is one of the quirks of history that this movie monster’s name was so often confused with his symbolic father and creator, Dr. Frankenstein. But in Karloff’s hands, the Monster turned out to be a greater star than the titular scientist who created him and ever since the name Frankenstein is synonymous with the monster, not the doctor.

“Here’s to a son of the house of Frankenstein.” Cheers to the son of the house of Frankenstein.

See you tonight!